At around Christmas last, I happened to come across a children’s fantasy in the television schedules. The film, “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe”, was, of course, no ‘first-timer’ to the children’s programmes; I’m sure it has been shown many times. I decided for the first time, ever, to watch the film, hoping all the time that my own children would never get to know what this rather long-in-the-tooth parent had been doing in his ‘spare time’. Now long out of their childhood, they might just begin to wonder whether I was going into mine – my second, that is!

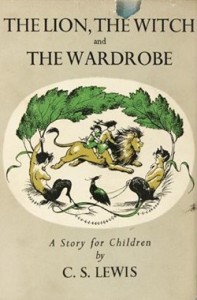

Many years ago, at home with the family, I remember that the children had been fascinated by the series, “The Chronicles of Narnia”, by C. S. Lewis, (1898 – 1963), though at that time, they really did not hold much interest for me, and I never got round to investigating them further, then, or in the pursuing years. Much later, I did come to learn that there were far deeper meanings to the characters and the fantasies, drawn so magnificently and so clearly by this ‘Oxbridge’ novelist, poet, literary critic, essayist, and academic. For the purposes of this short blog, let us here concentrate simply on his works for children – though, as we shall see shortly – he had important messages for right-thinking adults.

Having watched the film at Christmas – and with great interest, I may add – this new departure, for me, faded from my mind, only to be re-drawn just three weeks ago at Easter Time. Of course, this second ‘pointer’ to Aslan, Narnia and all that happened to the Children through the Wardrobe, all came about because of the great feast of the Resurrection, we Christians celebrate on Easter Day; many may then be prompted to ask about the link between these two quite different worlds. The answer, I trust, should become apparent in a moment or two.

For C S Lewis, Narnia is the parallel world, ruled for a hundred years by the evil witch, Jadis. Under her tyranny, the seasons have become perpetual winter, but with no Christmases. Many of Aslan’s friends and allies have been petrified – turned into stone – and, everywhere, the rallying cry is evil, rather than good. Quite by chance (and the fairy-tale path through an old wardrobe) four ‘normal’ children Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy, find themselves in freezing Narnia, and it’s then that their adventures begin. Mr Beaver tells the children that Aslan is on the move again, at the same time explaining that Aslan is the true King of Narnia, and that the children are to be welcomed as the true children of Adam and Eve – the chosen ones to end the rule of the White Witch (Jadis).

The children begin to explore and, as they do, the endless winter begins to thaw and Father Christmas appears once again, and hands out presents to the children. But all is still not right in Narnia. By means of trickery, and all over a bar of magical Turkish Delight, Edmund is unfortunately persuaded to betray his siblings, for which Jadis demands his life as forfeit. In the attempt to rescue Edmund, Peter slays Wolf, Jadis’ Chief of the Secret Police, and for this Aslan confers on Peter a knighthood. Secretly, Aslan offers to give up his own life for that of Edmund and Jadis accepts. Aslan is led to the Stone Table and the children, with the Beavers and other animals watch from afar. Jadis and her followers secure Aslan on the Table; he is then shaven and Jadis kills Aslan with her knife.

Her greatest enemy is now dead, and Jadis leaves with her army to prepare for war against the Narnians, convinced that she will win. Lucy, Susan, and a number of mice remove the bonds from Aslan’s body, but, as the Stone Table breaks, they find him alive and well, once again, thanks to a Deeper Magic from before the Dawn of Time. We are told, then, that the Witch came to Narnia only at the Dawn of Time, and had not known anything about the previous epoch. Aslan explains that this Deeper Magic can be invoked, but only when an innocent willingly offers his life in place of a traitor’s, causing death itself to be reversed until the victim is reborn.

Aslan goes to the Witch’s palace and, with his breath, brings the statues of her petrified enemies back to life. He leads them all to aid Peter, Edmund, and the Narnian army, who are fighting the Witch’s army. At the conclusion of the battle, Aslan leaps upon the Witch and kills her.

Clive Staples Lewis (known to friends, most of his life, as Jack) was brought up in Northern Ireland as an Irish Protestant. However, at the age of 15 he renounced all such ties and pronounced himself an atheist; his wry comment at this time, was to the effect that he felt: “very angry with God for not existing.” From then on, for most of his life, he seems to have had an on / off, love / hate relationship with religion, and connected subjects, but slowly, and with gradual steps, he came to once again accept Christianity as his true calling. In this he was helped by his timeless friend J. R. R. Tolkien and the writings of G. K. Chesterton, though throughout he described himself in the process as a “prodigal, dragged, kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance of escape.” He described his re-conversion to Christianity in his own book, “Surprised by Joy”:

“You must picture me alone in that room in Magdalen, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

But, we must now re-trace our steps and do as promised – to try and find the links that connect Aslan, Narnia, with those parallels in Christianity, otherwise one of the main tenets of the blog would have been allowed to escape. Aslan, of course, has his counterpart in Jesus, Our Lord and Saviour, who gave his life sacrificed on a cross, to save us, later to give us his greatest miracle of all – his Resurrection – and the greatest proof of his Divinity. Throughout the books of the series, Aslan also has God-like powers, in that he created Narnia with a song; there is a reference to the Emperor-Over-The-Sea, from which we must infer God the Father, and the reference in “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader”, can only mean heaven. Elsewhere, there are oblique references to a new Narnia and a new Earth (Book of Revelation), references to Jesus as the “Lion of the Tribe of Judah” (Rev 5:5), and as “The Lamb of God” (when first appearing at the end of “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader”.

And so, I now ask myself some pertinent questions. Was my childish excursion into fairy tales a totally wasted exercise? As to Aslan, Mr Beaver and other animals, and the White Witch, do they have anything to tell us? And what does Narnia have to say about good versus evil – an enmity that seems to pervade everything, always and everywhere? Was this an excursion into second childhood, with no wages at the end? Not a bit of it!

I enjoyed the film about Aslan and Narnia, and learned quite a lot about C S Lewis, his ideology and ingenious way of bringing home to children some of the truths most of us would wish to live by. The film, (and the books of the series), are all fantasy – parallel existences in a series of parallel worlds – but they amount to far more than just fairy tales. Certainly, even today, they are very relevant to today’s world (in which we all live), as conveying some stricter senses of morality; good versus evil was just as much alive, then in Narnia, as in our own world.

Overall, I was left with the distinct feeling that what I had been reading, what I had been seeing on the television, was as much about the author and the struggles he had had, ego versus ego, in endeavouring to come to terms with the existence of God, and with the many different beliefs held in Christianity’s widest senses. After trial and error, he had arrived at his own form of reconciliation. For me, this was what I called ample reward.

Socius