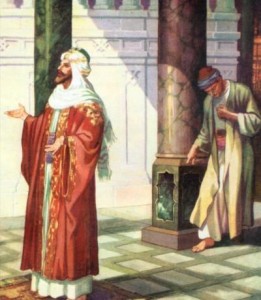

The Gospel for this coming Sunday – the 30th of the year – contains the famous parable of the Pharisee and the Publican. Both walked up the steep steps of the Temple to pray.

|

It is the only one of Jesus’ parables to take place in the Temple. The Temple is where God lives and, in the new world of Jesus, the ‘Real Temple’ made of ‘Living Stones’, is where God lives – the Church. It follows that the parable is meant for us. All of us have something of the Pharisee inside us that prevents us from being in union with God. Likewise, we all have something in common with the Publican – and thus we need to be careful, from two quite different points of view.

|

The reader would do well to look at the text of the story in Luke 18: 9-14. Below is a comment on this story from a friend, followed by some personal additions from myself (in italics).

“Two men: a just man and a sinner. That is how it is. One, a Pharisee, is perfect in observing the laws of God; the other, a Publican, is dishonest. Society categorises these two like that and the members of Jewish society in Jesus’ time are not wrong.”

Bear in mind the Pharisee came from those who followed the law scrupulously; praying regularly in the Synagogue, fasting, paying 10 per cent of his money to support the Religion, and furthermore, paying more for the many poorer people who refused, or could not afford to pay, their tithes. He is the upright, good religious man; he is the kind of man I might like to be, if I were a true disciple of Jesus, within the Church, within our own times.

The publican was a treacherous thief, and a ‘lackey’ of the hated Romans. He stole money, not only from the rich but, principally, from the poor. His job was to hand over taxes to the Romans and, as long as he paid the quota due, he could pocket all the rest – which he did. He was so hated that he was cut off from normal Jewish society. No ordinary Jew would welcome him into their home, or talk to him; he was regarded as totally unscrupulous, perhaps well compared, today, to a cruel loan-shark, who lends money to poor, vulnerable and desperate people; should they fail to repay their loan, he would use every kind of intimidation, including violent means, to regain his money with extortionate interest. According to Jewish law, by praying to God as he had in the parable, the publican was not about to get back into favour with the people. There were more steps for him to face. He would be required to repay all the money he had stolen, from every poor person, plus 20 per cent more. His appeal to God, made in desperation, was just the start of a long process. With such warnings in mind, ‘good Catholics’ need to be careful not to identify, too quickly, with the publican, as against the Pharisee, as maybe we are prone to do, on a scant first reading of the story. There is much more to the parable than just that.

|

For God, strange as it may seem, the judgement of society is wrong. Both come to the Temple to present themselves before Him, and pray.

The just man appears to pray to God, but, in reality, is looking at himself, his uprightness, his fidelity to the law. God does not truly exist for him: ego is the centre of his own world. He is trying to speak to God, and, in his own ‘tin-pot’ way, he considers himself the benefactor of God in the conversation – the one who is pouring out on God his own gifts.

The other has nothing to give – less than nothing – just his sins. He gives them to Him, without knowing that he is entering God’s heart. The good works of the Pharisee are an obstacle between him and God. The absence of good works – without reason for self-praise – in the case of the publican, allows him to establish a relationship with God. He does not dare to lift up his eyes, but God turns his gaze to him, because He sees before Him, a poor person who trusts, who is not making any demands, one who is simply abandoning himself to God.

Jesus ‘sinks his knife’ into the heart of the people – and into the structures of society; he undermines the certainties of behaviour and of conventions; he turns things ‘upside down’ and ‘inside out’, just so that they can be re-examined. Who knows if He is always in agreement with the ‘monumental tomb-stones’ to the benefactors of the Church, or with the statues erected to honour the ‘great people’ of civil and ecclesiastical life! What would he say about the roads, or city squares, named in honour of such people, I wonder!

Finally, though we may be tempted after just a first glance, we cannot say that Jesus has ‘canonised’ the publican, because it is not a real story; it is a parable; a lesson. However the ‘good thief’ truly did exist. What’s more, Jesus did canonise him!

The real key to understanding this parable lies in its preface:

“Jesus spoke the following parable to some people who prided themselves on being virtuous and despised everyone else”.

If we think like that, we have failed to have a true understanding of God – a great temptation for the Pharisees in Jesus’ day, and Jesus is saying that this particular Pharisee had ‘fallen’, as probably most had. If we are like that at all, we worship a false God, something referred to in the Old Testament as adultery. Our task is to examine ourselves and ask God for his gift not to despise anyone else – or any other group around us – to become more and more Godlike.

Father Jonathan