“Hello, my name is Wayne, and I’m 8 years old. I go to skool, but not this week as we are on half term. Don’t like hols so much, not much to do, but this week should be ok ‘cos on Thursday its Halloween an’ me and me mates will be out trick and treating. All me things are ready, pumpkin lantern, black cape and a frightenin’ old wizard’s hat. I even thought about gettin’ a stuffed black cat to sit on me shoulder, but I didn’t bother in the end. T’wud have made me look a bit like Long John Silver – but his was a parrot – and anyway, I’ve still got both legs. We’ll be out round the houses, knockin’ on doors, trying to make some dosh – shud come in handy for bonfire night. Shud be kool.”

|

“Hello, I’m Socius, and a little bit older than Wayne. And, as Thursday happens to be the Eve of All Hallows (Halloween), with Friday, 1 November, the Feast of All Saints, I thought I would write just a few lines about the two great feasts that occur at the beginning of November – All Saints and All Souls.”

When we come to Halloween – the Eve of all Hallows – we are looking forward to one of the most beautiful of feasts in the Church’s year. It is all concerned with that great communion of holy men and women who have died before us and found their way to heaven – the Feast of All Saints – a true cause for celebration. It also begins the ‘Season of Hallows’ which includes the Feast of All Souls. This occurs the following day, and here we pray for all those who have been forced to spend some time in Purgatory. It is our belief that these suffering souls cannot help themselves and so we are asked to pray for them to help them on their way to heaven, at the earliest opportunity. We believe that the saints in heaven also pray for the Souls in Purgatory – so the Holy Souls are being helped from two different sources – a wonderful way in which the communion of Christian souls works to the benefit of all.

I have always thought that this Community of the Church – those in heaven, those in Purgatory and those of us still living on earth, is one of the most wonderful (extended) families in creation – that is, until one then starts to question what has happened to our most beautiful celebration as time has gone by.

|

Halloween in Dublin

Halloween has its origins in the ancient Celtic festival known as “Samhain”. Pronounced “Sahwin”, this is a celebration of the end of the harvest and the gathering in of crops for the winter. The ancient Gaels believed that on October 31, the boundaries between the worlds of the living and the dead overlapped and the deceased would come back to life and cause havoc such as sickness or damaged crops. The festival in most cases involved bonfires to drive the bad spirits away, and such fires attract flies; they, in turn attracted bats – another traditional ’connection’ with evil. Masks and costumes were worn in an attempt to mimic the evil spirits or appease them. All of these come together to make up our present day traditions practised on Halloween, though most of them have been corrupted and no longer bear resemblance to their intended origins, which were, invariably, to encourage good, and drive away evil.

One of the practices, however, is of a much more recent origin, and here I refer to ‘Trick or Treating’, where young people go out visiting people, knocking on doors and then asking for treats. Originally, treats were mainly composed of sweets, biscuits, sweet meats, and the like, but these days are more likely to be about money. The essence of the ‘Trick or Treat’ lies in the threat that if the householder does not treat the callers in some small way , then they can look forward to tricks being played on them – not too far away from demanding money with menaces – I wonder! Now, I am aware of the fact that young children do not intend to take things that far, but I have seen evidence of older youths actually causing mischief for people refusing to give them money, and that’s a long way from what should be a Holy Night.

Of comparative recent origins, the ‘Trick or Treat’ has spread throughout much of the United Kingdom, Europe, the USA – also to many of the Arab countries of the Middle East. In England, the police have issued warnings about such practices, simply because of the ‘illegal’ aspects of ‘Trick or Treating’. In some parts of the USA, this particular evening is now known as ‘Beggars Night’ – again, a long, long way departed from the Feasts of All Saints and All Souls. We begin to depart even further when one considers the costumes the young people most often wear. Halloween costumes are traditionally modelled after supernatural figures such as vampires, monsters, ghosts, skeletons, witches, and devils. In my increasing years, I ask myself, just where are we going – the human race – and, in particular, our children?

Certainly, I have no wish to play the ‘Baron Hardcastle’ and come down like a ‘tonne of bricks’ on the young. I love to see the children and the young ‘let their hair down’ and enjoy themselves – enjoy life. However, there are many, many, good ways to create happiness and enjoyment for such young people; unfortunately, not all of them, today, are blessed in their methods, and in their intended ends. Halloween, in my humble view is one of those occasions where both ‘sail very close to the wind’, and there are very real dangers here of the devil’s power at work.

|

Perhaps, it has been out of a wish to counteract the evil influences manifestly abroad on Halloween, that in many countries, Christians practice measures designed to fight against the ‘black arts’. Many walk in processions (e.g. Poland), praying out loud, as they walk the night; In Spain, bells are rung to ‘ward off’ the evil spirits and remind believers to remember their dead in this ‘Season of Hallows’. Some practice abstinence (as in Canada), and in some countries, instead of meat, they resort to pancakes and colcannon. The Church, traditionally, observed Halloween by means of a vigil service, at which worshippers would prepare themselves, with prayers and fasting, for the feast day itself, an initiative once known as the ‘Night of Light’. After the services, suitable festivities and entertainments would often follow, and there would be organized visits to the graveyards where flowers and candles would be carried and left there in preparation for the All Saints’ Day. In Finland, because so many people visit the cemeteries on All Hallows’ Eve, to light votive candles, there they are known as ‘Seas of Light’.

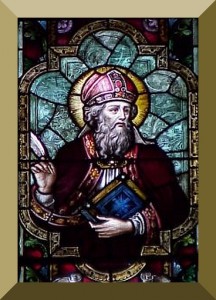

And, that last description says to me, very clearly, that this ‘Season of Hallows’ should be about light – not darkness; it should be about good – not evil; it should be about heaven – and not hell; it should be about life – and not corruption – it should be something like the following picture – this does an awful lot more for me than all the Halloween stuff!

|

All Souls Day in Dakhar.

God bless us – everyone!

Socius

NB. Readers of the blog may be interested to take in a quite beautiful article in November’s ‘Far East’ magazine (pages 6-7) entitled “The Holy Gathering” by Fr. Colm McKeating; in this, he describes the very special way in which the ‘Season of Hallows’ is celebrated in the Philippines – a celebration that is not at all like ours.